A different – and more effective – way to use discounts

Relevant topics Archive, Conversion

Would you rather have a 10% chance to get your product for free or a fixed 10% discount? And what does your customer prefer? Mazar, Shampanier & Ariely (2017) decided to investigate the attractiveness of this probabilistic free price promotions. Find out how to use the Las Vegas Gamble discount in your advantage!

For marketeers, the Super Bowl is always an interesting event. One of those times in the year when many US marketeers (or at least the ones who work with huge budgets) get extra creative to draw attention to their brand. My favorite example took place in 2015, when Volvo did this:

Volvo set up a contest through online video and targeted social advertising where people could win a Volvo for someone else by tweeting their name and using #volvocontest during any Super Bowl car commercial. With the idea to shift attention from the other car commercial to Volvo, they were a worldwide trending topic during the entire game. Oh, and they also received $200 million in earned media impressions and saw sales of their XC60 model increase with 70% in the month following the Super Bowl. Without even buying any of the most expensive advertising airtime of the year, which is why it was named “the greatest interception ever”.

Less creative (or at least less innovative) is to tie a price promotion to a big event like the Super Bowl. In 2014, Gallery Furniture in Houston promised customers who spent more than $6000 during their promotion period a full refund if the Seattle Seahawks would win the Super Bowl. A promotion they labeled as extremely successful, even though it cost them $7 million.

In the US, the Super Bowl and World Series are more often used for similar promotions. In Europe, big soccer events are the target of deals like this. A Belgian online retailer offered a refund for customers who bought a TV if Belgium would score more than 15 goals during the 2018 World Cup. (At the time of writing this post, Belgium has scored 8 goals in the first two matches. I wonder if some marketeers are getting nervous.)

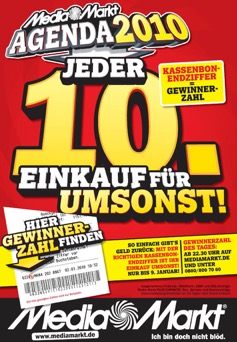

Between the many price promotion cases that are not specifically tied to an event, you don’t see promotions that feature a chance of getting the product for free very often. One example from the paper discussed here is from German retailer Media Markt.In 2010 they did a promotion where one in ten purchases would receive a full refund, but it was hard to find other examples. So, even though some marketeers seem to have tested the hypothesis that turning their promotion into a gamble is attractive to consumers, the belief therein does not seem to be universal. Mazar, Shampanier & Ariely (2017) decided to investigate the attractiveness of these probabilistic free price promotions. After some background on price promotions in general, this post provides the executive summary of their article and the practical implications.

Why are price promotions so popular, and should they be?

Even though price promotions have been shown to fail to bring new customers to a brand and to be unable to positively influence future buying behavior of current customers, they are still used very often. Sometimes more than half of a brand’s sales are made at a discounted price (so what is even the ‘normal’ price in that situation?).

Price promotions are probably so popular because results are easy to recognize. More items are being sold, and it happens immediately (while advertising effects are more long-term and harder to quantify). It may be important in some cases to simply turn inventory into money. And managers may have sales quantity targets they need to reach.

However, promotion effects end when promotions end. And because some consumers might stock up on a product, they might even cause a decline in sales right after the promotion. And if promotions are often used for the same product, they may even change consumers’ reference price.

Impact on revenue and profit

Furthermore, a discount needs to have a strong influence on sales volumes to make a direct impact on revenue and profit. Price elasticity theory from basic economics teaches us that when a discount of 33% leads to a volume increase of 33% (elasticity -1), this will lead to unchanged total revenue. This is not true, though. The impact on revenue depends on the discount level. And for higher discounts, a stronger effect on sales is needed. Make a simple calculation and you’ll see that with a 33% discount, you’ll need a 50% increase in sales to end up with the same revenue (elasticity -1.5). And with a 50% discount, you’ll need to double your sales to keep revenue the same (elasticity -2).

When it comes to profits, there is one more factor to consider: contribution margin. A discount will not suddenly decrease your costs. If your regular contribution margin is 50%, a discount of 20% will take 40% of your contribution margin. With this example, you’d need a 67% increase in sales to break even for the promotion (elasticity -3.33). If your contribution margin is 40%, the same discount of 20% would require a 100% increase in volume to break even (elasticity -5).

Increasing revenue with discounts is harder than economic theory suggests but still realistic. Increasing profits with discounts is much harder, though. A while ago, I had this discussion with one of my clients. I asked whether they took into account profit when determining price cuts. The response was that they are focused on market share and therefore calculated with revenue. This can be a valid strategic decision, but I would very much like to investigate buying patterns during promotions with their data.

Are we bringing new customers to the brand (and do they come back afterwards)? Are the discounts helping to ensure people choose us of over competitors? Or are we simply giving away margin to people who would have otherwise bought at full price? Science suggests the latter option to be a big part of it. But in e-commerce, where it’s very easy to compare a few retailers before making a purchase decision, I can imagine discounts are more helpful than in brick-and-mortar stores.

Increasing the effectiveness of promotions: turn them into a gamble

To summarize the section above, price promotions are much more popular than they should be. But that does still mean they are used often. So, can we make them at least a bit more effective, especially when it comes to impact on revenue and profit? To achieve that we need to make discounts more attractive to customers so that they’ll buy more. Without increasing the percentage discounted, because that would have a negative impact on revenue and profits.

Going back to the example, in the beginning, every 10th purchase for free at Media Markt, it made Mazar, Shampanier & Ariely (2017) wonder. Would consumers be more attracted to gamble-type promotions, e.g. 10% chance to get their purchase for free (and a 90% chance to pay the regular price), compared to guaranteed, fixed percentage off discounts?

In 5 different experiments (field and lab, using different products, price levels and a range of discount levels) they found consumers consistently favored the so-called probabilistic free price promotion over a sure discount of equal expected value. The difference was strongest for the lowest discount percentages and found for discount levels up to 67%.

This happened when consumers could choose between both types of discount, but also when only one of the promotion types was offered the probabilistic free promotion won. More consumers made use of that promotion and average basket size was higher, leading to more sales in two different ways.

So, yes, a discount in the form of an x percent chance to get the purchase for free can lead to more sales than a fixed x percent discount.

What to do with these findings?

Although five different experiments were performed, this is still only one study. Offering a probabilistic free price promotion seems to be a more effective way to use discounts, but ideally, you should test this in practice and see if you can replicate the results.

Also, it might work best if you’re a first-mover using this promotion, as the effectiveness of gamble-type promotions can be due to a novelty effect. The authors tried to control for that, but I’m not fully convinced they did enough to be able to rule it out. This just to say that if you can replicate these results, you might want to re-test if these promotions become more popular and the novelty wears off.

Conclusion

Discounts are not often a very profitable marketing tactic, but still they are very common. That said, probabilistic free price promotions can lead to higher sales than fixed discounts. So, if you are making use of discounts anyway, this Las-Vegas-style-discount is worth a try.

In any case, calculate sales levels needed for your discount to increase total revenue and to break-even, and use that information in your evaluation of price promotions.

By the way, with this article, we decided to offer a special promotion on our newsletter that will inform you when a new article is posted on New Neuromarketing. You can now choose between a sure 100% discount on the price of €0, or a chance of 100% to get your subscription for free when you sign up.

Further Reading

-

The Boomerang Effect of Discounts - Why Lower Prices Can Backfire and How to Avoid a Decrease in Sales

Discover how to improve sales by applying the right discounts for the right products.

-

How to set discounts for various related products

Chocolate bars, everyone has at least one in their kitchen cabinets, for those rainy evenings on the couch. Yes, (nearly) everyone loves chocolate, but some companies thrive and others…well…have a harder time trying to sell their chocolate bars.