The Boomerang Effect of Discounts - Why Lower Prices Can Backfire and How to Avoid a Decrease in Sales

Relevant topics Archive, Conversion

Discover how to improve sales by applying the right discounts for the right products.

It’s a common thought that all products with a discount sell better. However, recent research found that this might not always be the case. It all depends on the kind of product you're selling.

Imagine that a bar of chocolate is on display at comparable supermarkets. The chocolate bar at supermarket A is on sale for 1.8 $ (a 10% discount) whereas the same chocolate bar at supermarket B is sold for the undiscounted original price (2 $).

What do you think: Which of the two bars has a higher likelihood of being sold? The chocolate bar with a 10% discount because it’s cheaper, right? A recent study revealed that the reverse is the case. Low price discounts can even decrease the purchase likelihood.

The Psychology of Buying Behavior

In order to understand why discounts don’t necessarily have a positive effect on purchase likelihood we have to consider the factors that initially motivate purchases. These factors can be separated in two different scenarios.

In some cases certain products are bought to serve an inherent need, bread for example because we feel hungry, or toothpaste because we want to brush our teeth and ran out of it. In this case we call the purchase an essential purchase because it serves an essential need. A few essential example categories that Albert Heijn, the leading grocery shopping chain in the Netherlands, uses:

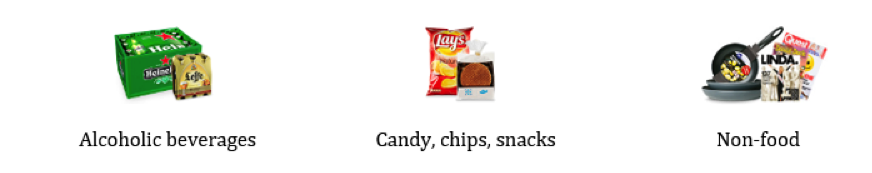

In other cases, products are purchased merely because they seem like a good deal and not because they are needed at that specific moment. A good example is chocolate, which is not an essential necessity for most consumers. This kind of purchase is referred to as a nonessential purchase; it is optional and mostly unplanned. Again a few nonessential example categories from Albert Heijn:

According to Cai, Bagchi & Gauri (2015) essential and nonessential purchases are driven by different values: acquisition and transaction. Acquisition value on the one hand refers to the net gains derived from a purchase, influenced by the benefits consumers gain and the money they lose by buying a product. Transaction value on the other hand relates to the pleasure associated with the purchase.

When it comes to these values there is a crucial difference between essential and nonessential purchases. Whereas for essential products both acquisition and transaction are almost equally important values for decision-making, the decision-making process for nonessential purchases is influenced primarily by transaction values; the pleasure associated with a good deal. In order to buy nonessential products, consumers need a good justification, as they are actually not really needed.

Therefore consumers evaluate transaction value based on the product’s price. Consequently the pleasure they get from it could be such a justification: A bar of chocolate for 99 cents? Not too bad, seems like a good deal.

Newneuromarketing is looking for new authors! Are you up for the job?

Send us an e-mail at tim@newneuromarketing.com to become an author and start spreading knowledge.

Why Discounts Can Backfire

So what happens when the price of a product is lowered for a limited period of time, by 10% or less? For essential products a low discount, which is defined as 10% or less, increases both the acquisition value (more net gain) and transaction value (more pleasure) and therefore increases the chance of a purchase. Sounds great!

However, it doesn’t work this way for nonessential products. The low discount actually lowers the transactional value of nonessential purchases and therefore also lowers the purchase likelihood.

The simple explanation for this effect is that a low (vs. no) discount provides new information: The difference between the original and the discounted price. As the discounted price is not much better than the original price, the deal is not perceived as great. Consequently the consumer would rather wait for a better deal in the future.

This is obviously different for essential products, as consumers need the product right now, and not sometime in the future. That’s why they are satisfied with any discount as even a low discount is better than no discount.

Important remark: In general this effect only holds for low-priced products when the package size is small. If you spend €250 on a package consisting of 100 boxes luxury Belgian chocolates, even a relatively low discount of 10% would have a significant influence!

How to Avoid the Boomerang Effect

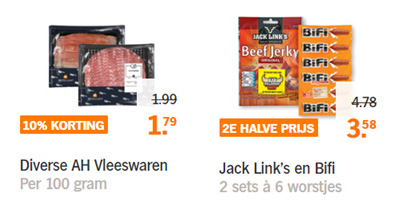

Let’s turn back to the chocolate bar example to translate these interesting findings into real life implications. We learned that the chocolate bar with no discount has a higher likelihood of being sold than the chocolate bar with a 10% discount. If we walk through different supermarkets to check their discount offers, we will notice that some of them actually do a good job at applying the principle. Albert Heijn for example applies a lower discount on the more essential sausage products and a higher discount for the nonessential snacks:

As you can see: Both products have a comparable ingredients, a comparable target group but a different discount. 10% for the essential product versus 25% for the nonessential product.

Other supermarkets do make the mistake of applying low discounts on low-priced nonessential products. Listed below are two examples for chips, according to the theory a nonessential product category.

On the left side we see an example from Plus, another supermarket from the Netherlands. They apply a low discount of less than 4% on Cheetos. The other example is from Jumbo, yet another Dutch grocery shopping chain, who applies a 10% discount. More than the 4% from Plus, but according to the theory still too little to heighten the chance of purchase.

But do you notice another difference between these two examples? They use a different way of framing the discount. While the left supermarket shows the new price, the other supermarket shows a “2 for €2,00” button they use throughout their site. This might distract consumers from the actual height of the discount and therefore keep them from calculating their advantage. In other words: Instead of lowering the transactional value, they probably even increase it.

Another possible strategy could be to combine the scarcity principle with low discounts for nonessential products to prevent customers from postponing their purchase. By convincingly communicating that the discount is a once in a lifetime offer, customers might be less likely to wait for a better deal in the future.

A third possibility to weaken the boomerang effect of low discounts is to frame nonessential products as essential. Snacks, for example, are only nonessential as long as you don’t host a party tomorrow. Chocolates are only nonessential as long as it’s not Mother’s Day tomorrow. The consumers perspective is of utter importance.

Finally you could also offer a different advantage for customers who buy low-priced nonessential products, instead of a monetary discount. Think of bonus loyalty points for example: “Buy Lays chips and get double bonus points” or “Buy Milka chocolate and earn 50 extra air miles”.

Take Home Points

- Get to know your target group and understand which products are essential to them, and which aren’t.

- For essential products: Use low (or no) discounts for essential products and keep in mind that these purchases are motivated by both transactional and acquisition value

- For nonessential products: Increase the consumers feeling that they get a good deal by using high discounts, as the primarily driver for these purchases is transaction value.

- If you still want to assign low discounts for low-priced nonessential products, choose a strategy to weaken the boomerang effect, for example by framing the product as being essential, applying the scarcity principle or offering loyalty points

What Do You Think?

An interesting question would be whether this effect differs for different cultures and countries. The Dutch for example are known for being thrifty. What do you think: Is the effect especially strong because Dutch people always try to get the best deal?

Further Reading

-

The Sunlight Effect: How daylight might make you money…

Economic theory predicts that people’s spending activities do not vary with environmental conditions, such as seasons and weather-related factors. As neuromarketers, we know better than that. It’s hardly surprising we all pay more for ice cream during the summer and the sales of ice cold beers skyrocket when there’s more sunlight. The price dynamics of these nondurable goods make economic sense in the light of increasing demand. However, you wouldn’t expect to find such patterns in durable goods like art, but that’s not what science discovered…